Formula 1 wouldn’t have been the same today without him

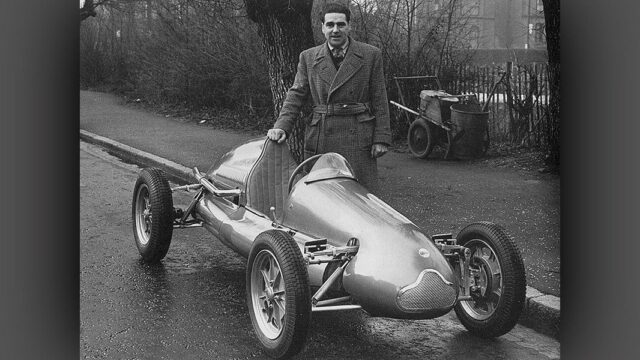

The label that marks Mini's performance models isn't there by coincidence, but to honor a man who changed Grand Prix racing in the 1950s: John Cooper.

At some point between the two World Wars, a young boy called John was bullying the milkmen of Surbiton on early mornings as he drove a 175 cc two-stroke Villiers engine-powered kart built by his father, Charles Cooper, a racing mechanic.

Still recuperating after the Second World War, Charles Cooper and his son John – who left school at the age of 15 to become an apprentice – ran a small business focused on car sales and a service garage. It was where they built their first racer from a sketch drew in chalk on the workshop's floor.

The car used the front suspension from a Fiat Topolino and the driver sat up front, while the back-positioned engine – a V-twin JAP (JA Prestwich Industries) motorcycle unit powered the rear wheels via a bike gearbox and chain system, spawning what we call a rear-engine vehicle.

The low-priced race car recipe proved successful and rapidly attracted a swell of private motorsport-involved parties, and the high demand saw the Coopers build their own car firm in 1948: Cooper Car Company.

The 1950s came and with them another spell of success followed through for John Cooper and his father. As a small adage, although Auto Union's Silver Arrows used a rear-engine configuration back in the 1930s, the practice went extinct until Charles and John brought it back in the 1950s.

Their rear-engined 500cc racers were causing a stir in Formula 500 and the Coopers quickly became a dominant force in Formula 3 and Formula 2, before making the final step to Formula 1.

"My God, that thing can really go!"

That's what drivers said after they had a go at the Cooper 500. But what really helped the Coopers make a name for themselves was Stirling Moss' dramatic victory at the 1958 Argentine Grand Prix.

Moss joined Rob Walker's private team and agreed to drive a Cooper powered by a 2.2-liter Climax engine. Maserati and Ferrari had 2.5-liter engines, but the Cooper was lighter on its feet than its cumbersome competitors.

"We certainly had no feeling that we were creating some scientific breakthrough! We put the engine at the rear because it was the practical thing to do."

Fangio and his Maserati were leading Moss by just a second during practice, yet the Cooper's nimbleness and lightness translated into minimal tire wear.

Of course, Moss' alien handling skills also helped out, but this behavior inspired Walker to come up with an eccentric race strategy: the car would attempt a non-stop run, without any pit stops.

As Moss was running behind Juan Manuel Fangio (Maserati), Jean Behra (Maserati), and Mike Hawthorn (Ferrari), he began charging for the podium but also looking to preserve his tires.

He had already passed Behra and Hawthorn when Lady Luck finally smiled as Fangio stopped to refuel and change tires.

In spite of the growing canvas spots on the Cooper's tires, Moss marched on and crossed the finish line ahead of Luigi Musso (Ferrari), Hawthorn, Fangio, and Behra, who followed him in this order.

Although the victory was mostly attributed to the tactics employed by Cooper-Climax, it would mark the beginning of the end for the front-engined race car. By the end of the season, many teams would see this layout as a fossil and subsequently ditched it.

In the following two seasons (1959 and 1960), the Coopers gained invincible status with Jack Brabham behind the wheel.

Before the 500cc initiative and Cooper's cheap-to-build and prolific rear-engine layout, motorsport was the wealthy man's hobby.

Yet despite unmatched agility, the Cooper was far from flawless, as its basic chassis design used curved tubes – a poor design solution – instead of straight tubes simply loaded in tension or compression.

John Cooper, although notorious for his sense of humor, was seen as a man who "never blew its own trumpet."

He never bragged, remained humble and always considered that his idea of placing the engine at the rear of a race car came out of necessity, rather than genius.

John Cooper passed away aged 77 on Christmas Eve in 2000, after he was awarded the Order of Chivalry of British Constitutional Monarchy (CBE) earlier that year, in April.

Photo credits: Cooper Car Company